Spine surgeons begin their careers as either orthopedic surgeons or neurosurgeons. Most training programs in spine surgery around the world are based on surgical apprenticeships through fellowships at hospitals specializing in spine surgery, supplemented by continuing medical education activities. Very few of these fellowships have a curriculum or formal training program.

The starting point for a curriculum planning process using entrustable professional activities (EPAs) is analysis of the professional work of the specialist medical practitioner. This analysis identifies the essential activities that can be entrusted only to those who have acquired the requisite abilities to work independently in a given health care context to achieve a desired outcome. In a training program, EPAs can be subdivided into entrustment milestones where trainees move from high levels of supervision to more autonomous levels as they are deemed to have gained the necessary competencies.

The word curriculum has traditionally meant a course of study offered by a school, comprising the body of knowledge that is to be transmitted by teachers to students. More recently it has come to mean the experience of learning, recognizing that the focus is on what the learner experiences during the process of learning and acquiring expertise. Put more succinctly, a curriculum can be defined as a program of learning that describes how expertise in a field of study is obtained. The syllabus is a list of the competencies to be acquired, as defined by learning objectives, educational methods, learning resources, and assessment tools. The curriculum is the roadmap showing the pathway to competence and the syllabus is the navigation system showing where and when to make the turns.

For medical education, competency-based frameworks have replaced time-based systems in preclinical, clinical, and specialization pathways. Core competencies that reflect the abilities required for clinical practice upon graduation are defined so that they are observable, measurable, and assessable. Progression in the training program requires sequential acquisition of the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes. But problems can arise if these competencies are observed and assessed in isolation from the context in which they will be put into practice. Just ticking the boxes by achieving a minimum standard in each element does not necessarily mean that an individual can put everything together in a real-world situation that requires clinical judgement, decision-making, and safe practice.

The AO Spine Education Commission decided to use the framework of entrustable professional activities, beginning with the final level of autonomous practice that describes what spine surgeons do in their day-to-day professional lives and the core competencies they must have to treat patients with spinal problems in order to achieve good outcomes.

EPAs were developed by Olle ten Cate, professor of medical education at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, to operationalize the link between theory and practice in postgraduate medical education. They are essentially competencies in the context of the workplace: units of work in a given clinical specialty that are entrusted to practitioners who have the necessary abilities. The work activities describe the tasks and responsibilities of professional practice. The units of work are mapped to clinical and nonclinical competencies that individuals need to master in order to perform the professional activities.

In postgraduate training programs, trainees gradually assume more responsibility for patient care while under supervision. EPAs allow entrustment decisions for progression to be based on development milestones that reduce the level of supervision required until the trainee is deemed to have reached the level of independent practice for that EPA.

When using EPAs for curriculum building, it is important to consider the breadth and depth of the work activities. Starting with breadth, EPAs should describe all the activities of independent practice at a particular level of development (eg, at completion of internship or completion of specialty training). For clarity, a small number of EPAs is better, so the idea of “nested” EPAs has been developed. A broad EPA such as managing inpatients might be composed of many specific EPAs such as monitoring vital signs, documenting daily progress, planning for discharge, etc, which define the depth of the overarching EPA. Most EPA-based curricula contain between ten to 30 broad EPAs, each containing nested, specific EPAs which describe the transition points for progression of responsibility.

An EPA should describe a unit of professional work that links the activity to the personal abilities of the individual who will perform the work and the process of progression during the acquisition of those abilities. The best way to define the EPAs of a specific medical specialty is to involve those who are experts in the specialty through group meetings, surveys or a Delphi process. Once the EPAs are defined, they should be scrutinized for content validity: Is the EPA really work or is it something else?

For the AO Spine Curriculum, we used a nominal group of spine surgery experts from around the world to create a list of EPAs, then refined the list through an iterative Delphi-like process over several on-site, face-to-face meetings and virtual meetings.

The opening list looked like this:

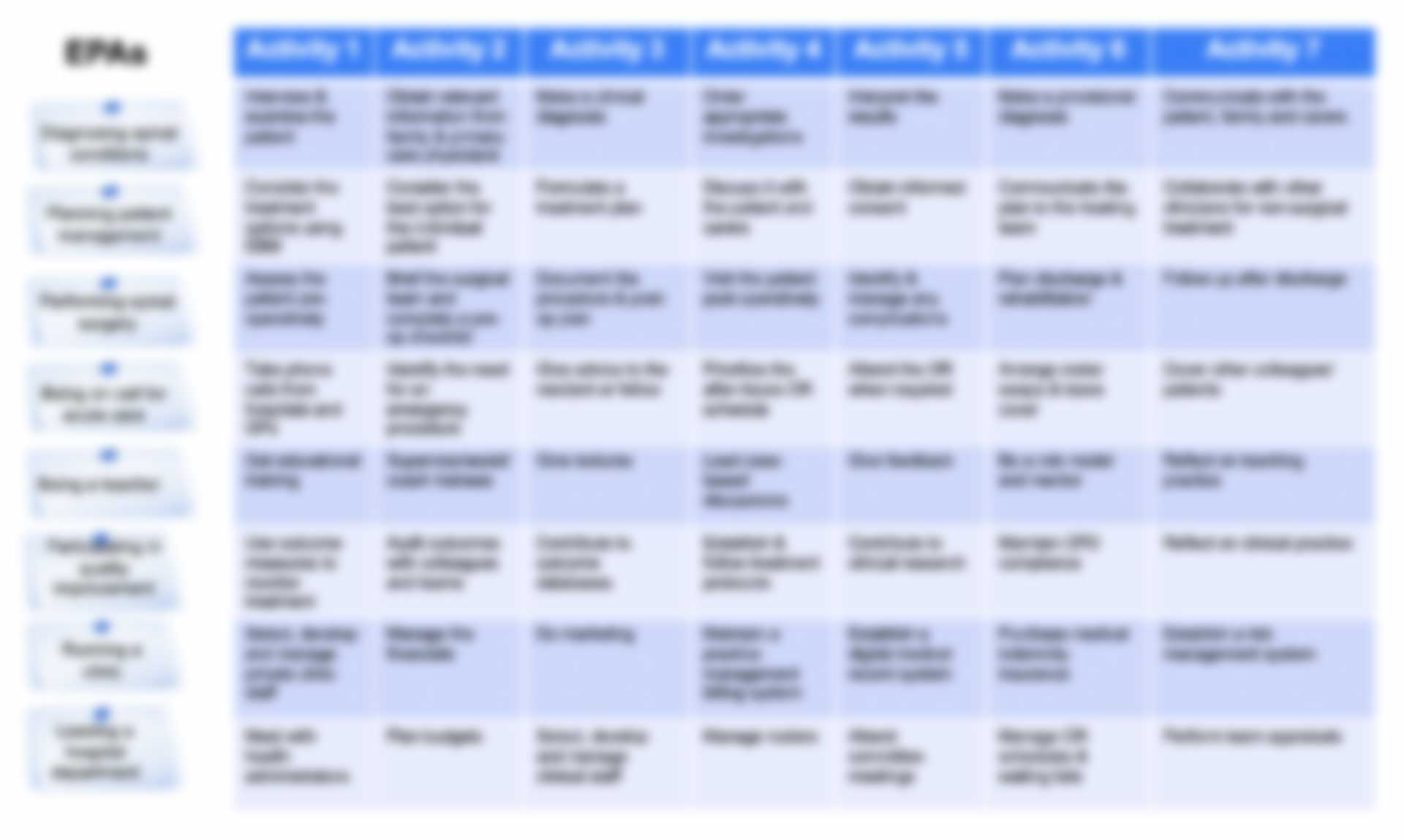

At the end of the process, a core group of seven EPAs was agreed upon:

Each EPA is elaborated by key competencies under the domains of clinical conditions treated by spine surgeons:

All AO Spine educational events are linked to the curriculum. Event planning starts with an assessment of the learners’ needs for a specific topic. The curricular competencies to be covered are specified before the event so that learners can provide input into their current and desired levels of experience. This informs the pre-event preparations and reinforces the link between the event content and the AO Spine curriculum. Each event is aimed at a specific domain or competency within the curriculum, and the event content relates directly to the learning objectives, learning methods, and resources of that particular educational experience.